Here I discuss my observations between the four fields: linguistics, cognitive psychology, Buddhism and Daoism. Each section will be a topic that involve at least two of them. Note that my understanding on linguistics is not very strong.

Misunderstanding in communication

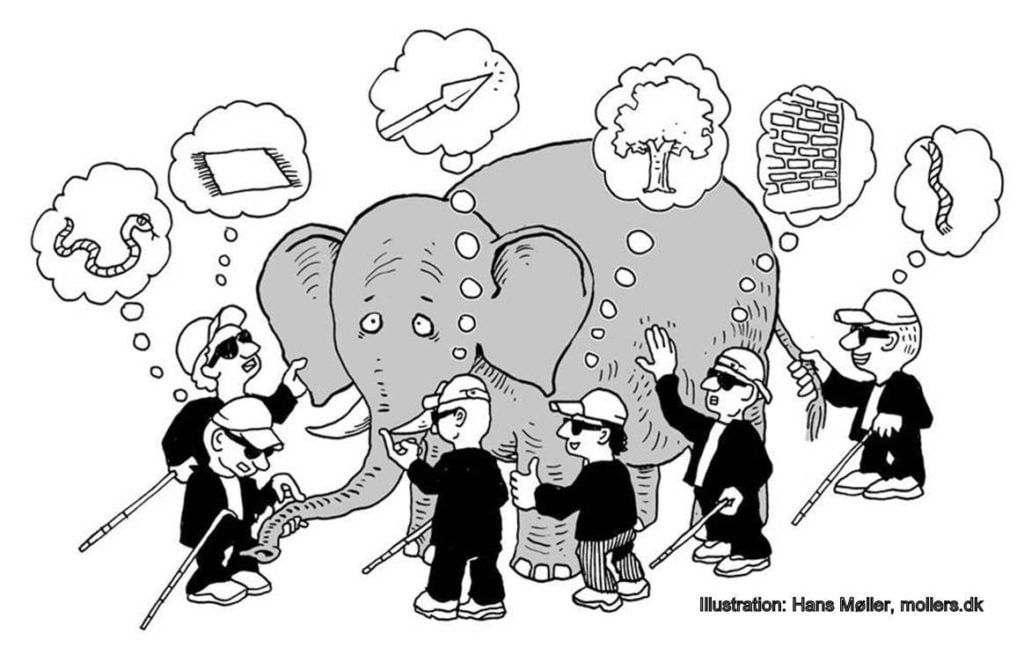

In the parable “The blind men and the elephant”, the concept “elephant” is defined as “snake”, “tree”, or “spear” by different blind men. Due to their blindness/misunderstanding/misinterpretation, they accidentally attach wrong senses (or sememes) to the word, and then they have trouble to identify the problem inhibiting them to communicate. Because for one form there are different meanings linking to it, the word “elephant” a kind of polysemy.

Since this is not a true linguistic polysemy, I will call it as “generalized polysemy”, “temporary polysemy” or “cognitive polysemy”.

When this kind of polysemy happens, psychological tendencies like illusion of transparency, naïve realism, egocentrism or self-conscious emotions in both sides will make the conversation not go anywhere. It’s not that they don’t want to listen to others, but it’s that they really don’t know what is wrong with their observations. Their curiosity to confirm their observation demanding them to stay on it before considering any other one. Therefore, the ability to be aware that all of our words are polysemies may be critical to solve this frustration.

It seems that Buddhism is relevant to this interaction between cognitive psychology and cognitive linguistics, because, well, the parable is a Buddhist story. To be specific, I think concepts like sunyatta, dharma, dependent origination can help us to build a specialized framework for misunderstanding in communication. By being aware of that, we can always ask Socratic questions to clarify or help identify incorrect understandings, even when we have strong emotions to the information.

Ineffability

When a person has been familiar with something, they have possessed some tacit knowledge about it. By definition, such knowledge is extremely hard to even aware of it, let alone verbalize it in a succinct manner. I think Laozi had this idea when he wrote “the Dao that can be explained is not the Dao”. People who don’t try hard to explain themselves also have this intuition too.

Metaphor can help express tacit knowledge. By mapping from one domain to another, the knowledge is transformed and transcended, bringing us from one perspective to another. In the new perspective, you will know where to explain next, and thus don’t feel that your understanding is inexpressible anymore. Gradually, your explanation will be organized in a perfect combination of words, so that people having no former background can see the order from the chaos as you see it.

However, it is possible that the listeners have tacit knowledge also. Just a little different subtlety in both sides and they will talk at cross purposes without realizing it. In that case, we return to the case of the blind men and the elephant. The only way to solve this is that one of them verbalize their subtleties, which is almost impossible since they are too focused at correcting the understanding of the other.

Detailed article: Making concrete analogy and big picture

Wuwei

Wuwei, as how I understand it, has these understandings, depending on the context:

- You do something because you are born for it and do it without wondering why you need to do or learn how to do it (e.g. trees produce oxygen not because oxygen is needed for animals, but because they need photosynthesis)

- When you are doing it you are being present in the moment, and allow life to lead you to something unexpected, yet you do not get confused and unprepared when the unexpected occurs

- Your action has been simplified to its most basic parts so it can be accomplished in the most efficient and effortless ways

- You don’t need to do anything because you see the order from the chaos, and you see the big picture from above

- You do something impossible or insane with confidence and fearlessness, because you have the knowledge and can improvise with any unexpected event (e.g. sailing into a storm with a smile, running into a burning building to rescue life)

None of these is about “non-doing” in any sense of the word. Therefore, I think we should make a break with that translation/understanding, and should only translated it as “effortless doing”. The old understanding is the reason why it is so easy for a Daoist to have confirmation bias, even though they are totally against them.

Although Daoism is to emphasize the limitation of logic, that its ability to capture reality like how our hands hold sand, only using the statement “the Dao that can be understood is not the Dao” as absolute answer to any attempt to analyze something will make it a thought-terminating cliché. This can also be interpreted as a lack of interest to the listener, and depending on the context they can be perceived as trying to build a mystical halo on them. This can also be a convenient trick to protect self-image and get away with using rationality. This can also lead to an extreme that analysis is bullshit, and only feelings are correct, which can nurture their egotism and naïve realism, covered in the form of Daoism.

Polysemy

1

In cognitive linguistics, strong polysemies (those have completely unrelated meanings, like bat or bank) can be identified with the test “X is not X” and see if it makes sense or not. For example:

A bat is not a bat. A bank is not a bank.

What about weak polysemies? We can still use negations to strip down irrelevant sememes. For example, to explain a derivation of the word “head”, we can use this:

A head in here is not a body part

and then we can understand that the word should mean a top person of an organization. I think the existence of negation can indicate the existence of polysemy.

Eastern philosophical texts seem to use paradoxes to overcome conceptualization and dualistic, and I find in them lots of negations. For example in Nagarjuna’s Middle Way:

An action does not possess conditions; nor is it devoid of condition.

Conditions are not devoid of an action; neither are they provided with an action.

or Laozi’s Daodejing:

The Dao that can be spoken is not the Dao

I think we can study these texts linguistically.

2

When a blind man hears someone says the idiom “the blind leading a blind“, what should he do? Living in a society that is constructed specially for non-blinds, there are so many things that simply out of his ability. Thus, being a blind seems to be a stigma. Yet, that stigma is fair, after all. He understands that they mean no harm to him when saying that, but that truth is still bitter. Yes, the truth should be bitter, but people say that because after the shocking episode, gradually they can find a way to improve themselves. In his case, there is no way he can use that information to improve his disability.

But if he realizes that in their perspective, there is simply no concept about him, then he will realize that he is distorting their words. He starts seeing that his version of blindness is not their version of blindness. In his world, being blind is simply like having no biological sensor to detect Earth’s magnetic field. He just feels nothing, and really doesn’t feel the need to have that sensor. He’s good.

If he is in good mood, he can even recall how he and his peers help each other. This will gain him more self-worth, and place him in the position of having more knowledge than the non-blinds. When the non-blinds have a new perspective to think about it, the negative cycle of shame and becomes positive.

The feedback loop between the non-blinds’ ignorance and his shame on his disability. The more he is shameful (an emotional process), the more he is unable to think about how he is fine with being blind, and the more the non-blinds still don’t know why that statement is not applicable on him.

When he realizes that his version of blindness is not their version of blindness, then he has “polysemized” the word blindness.

Yinyang

Yinyang is usually illustrated by dyads like black vs white, high vs low, or male vs female, but I think its mechanism is best illustrated via in double negation and litotes.

I cannot describe this phenomenon precisely, because I haven’t read enough linguistics. However, from my experience, using double negation on any statement that tends to critique an idea will reveal hidden assumptions and help us putting ourselves into the perspective of the other side. In the examples below, the first sentences are the premises, and the second ones are produced by using double negations on the first ones:

- In the argument between Daoism and Confucianism, it seems that Daoism acknowledges the necessity of benevolence, but just emphasizes that it should be discarded when it doesn’t need. I think we can say the same with Confucianism, in that it acknowledges the necessity of un-benevolence, but just emphasize that it should be there when it is needed.

- Wanting to be purposeless is good, but it is still a purpose. But knowing how to be purposeless will make you be purposeless without wanting to be it.

I agree that this doesn’t seem to be relevant to double negation at all, but during the reasoning process I always have a feeling that it is.

* * *

To summarize:

- Communication cannot get to anywhere because the partakers aren’t aware that they are talking at a polysemy

- Tacit knowledge makes an obvious thing ineffable. Metaphors can help express it

- Understanding wuwei as “non-doing” can nurture psychological issues

- There are lots of negations in Daodejing and Middle Way

- Polysemy can help protect one’s insecurity

- Yinyang is best understood with double negation, not dualism

Accompanying with this article is a proposed framework to illustrate and visualize Buddhist concepts like sunyata, nirvana, dharma, the transformations, transcendences and distortions of perspectives, and discuss it various applications. You can read its research proposal.

Martin Hilpert, A Course in Cognitive Linguistics: Categorization

Leave a Reply